I’m going to get a bit inside baseball in this post, and talk about startup stuff.

Those of you who are steeped in recent startup lore know the #1 job of a startup in its earliest phases is to discover product-market fit. First named by Benchmark founder and Wealthfront CEO (and my Stanford GSB professor) Andy Rachleff, product-market fit depends most of all on finding or creating a great market. As Rachleff says:

“When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins. When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins. When a great team meets a great market, something special happens.”

We’ve made a lot of progress on finding that market — but we’ve also made some mistakes. I thought I might share what we learned so that other entrepreneurs (especially in Enterprise SaaS businesses) might be able to avoid our mistakes. (Don’t worry, you’ll make your own mistakes 🙂 )

A New Product Category

Before talking about our mistakes, let me say a bit about our product strategy. AVATOUR is more than a new product; it’s really a new product category. This was a deliberate decision on our part. I agree with David Sacks and Christopher Lockhead on this:

Following this game plan, we’ve created a new product category called “Remote Presence.” Remote presence (at least as we define it: immersive and multi-party) wasn’t even possible a couple of years ago, so we have the opportunity to create a new market for ourselves. That’s great, but the thing about creating a new product category is that the people who might want to buy your product don’t even know they need it! This makes it a bit tricky to find buyers, at least at first.

We have a pretty clear hypothesis about the kind of people who should want Avatour and why: Avatour is a new alternative to travel for people who make decisions about places. That’s a pretty broad group, though, crossing several verticals and markets, some of which we had some experience with and many of which we didn’t. So our initial goal was to learn about the market by getting some early users.

Towards that end, we launched AVATOUR with a small beta program in September 2019, eventually comprising 10 customer-users across several sectors and use cases we wanted to get to know better.

And that’s when we made some mistakes.

Mistake #1: Unpaid Trials

Since we had so much to learn about so many different sectors, we thought it was most important to get users quickly, no matter what. So we made the decision to offer a 3-month trial completely free for our highest priority verticals. Makes sense, right?

No. Don’t do it.

Yes, it can be hard to convince a buyer to take a risk on something new that they don’t entirely understand. But nonetheless there’s at least a couple of reasons why you should insist on getting paid something for trials.

Cash signals willingness to pay

The first reason to insist on paid trials is because each paid trial consists of a crucial piece of information: willingness to pay.

If a buyer isn’t willing to pay something to discover whether your product can address a serious source of pain for them, then their pain isn’t really that serious. That buyer – and that type of buyer – probably is a poor target. That’s useful information, and 3-5 responses from similar buyers probably means you need to look elsewhere.

If, on the other hand, a buyer will take a chance and put their credit card down for an unproven product from an unknown company, that’s already a pretty good sign that you’re on to something, and that similar buyers in the same sector might make the same choice.

That said, while a trial payment is a positive signal, it doesn’t contain an enormous amount of information. It’s really just a binary signal – yes or no. Prospective customers are unlikely to be able to tell you exactly how much a new product will be worth to them until they actually use it. (This is especially true for new product categories like ours.) So don’t try to force it. Don’t sweat the actual cost of the trial, and don’t think of the trial cost as an input to your product pricing strategy. The goal is simply to get the buyer to give you that bit – to show that they’ll pay something. As a result, you should keep the trial cost well below the limit that your buyer can authorize individually — perhaps the cost of a meal out with his or her team.

Free trials waste your time

An even more important reason to insist on paid trials is to avoid users who will waste your time.

The most precious thing you have – in your startup and in your life – is time. And even more important than the signalling function above is the fact that you have only so many hours in the day to service your customers, and to learn from them. Free trials aren’t free; they cost you.

Trial users who don’t pay anything have little incentive to engage with you and your product. They’ll put you off, fail to return emails, and possibly not even use the product at all. You’ll waste a bunch of time servicing them, and not only will you not get a sale in the end, you won’t have any more information than if you had just walked away in the first place.

We learned this the hard way. We were so psyched when we signed a healthy handful of Beta customers to unpaid Letters of Intent in our first two weeks after release. And sure, some of them jumped right in and started using the product, giving us solid feedback. But others … didn’t. After repeated calls, emails, visits, and cajoling … two of them churned, and only after we told them we were cutting them off. Those were two slots that would have gone to real customers if we had just insisted on being paid for trials.

Now, if you’re in a consumer space, possibly it’s a whole other story. But for enterprise SaaS, my advice is unequivocal: don’t do free trials.

Mistake #2: Enterprise & DIY Don’t Match

One of the big advantages of Avatour is that it uses inexpensive, off-the-shelf hardware like the Oculus Go and the Insta 360 One X. This kind of hardware has only recently become available – a few short years ago, Avatour would have required tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of capital expense. (We should know; we were part of the team that built the $60,000 Nokia OZO.) It’s not too much to say that our entire product category is enabled by this new hardware.

As a scrappy, bootstrapped startup, where every dollar counts, we hate paying markups. We DIY just about everything. So we made the classic mistake of projecting our own preferences onto our Beta users. We figured they would want to buy the necessary hardware from discount vendors rather than paying us a markup. (Also, we really, really didn’t want to be a hardware company.) So we sent every one of our new Beta customers a shopping list.

This … didn’t work.

Customers bought incorrect things, forgot to buy others, had problems finding some. We discovered we aren’t actually “compatible with any Android device” when customers brought random devices we hadn’t tested. And through all this, precious time dripped away, along with the enthusiasm our customers had started with.

Enterprise users don’t do DIY. Saving a couple of hundred bucks isn’t worth a single hour of their time. And wasting their time is a sure way to sour them on your product.

Luckily for us, these customers stuck with us as we helped them assemble the correct hardware. But we learned our lesson.

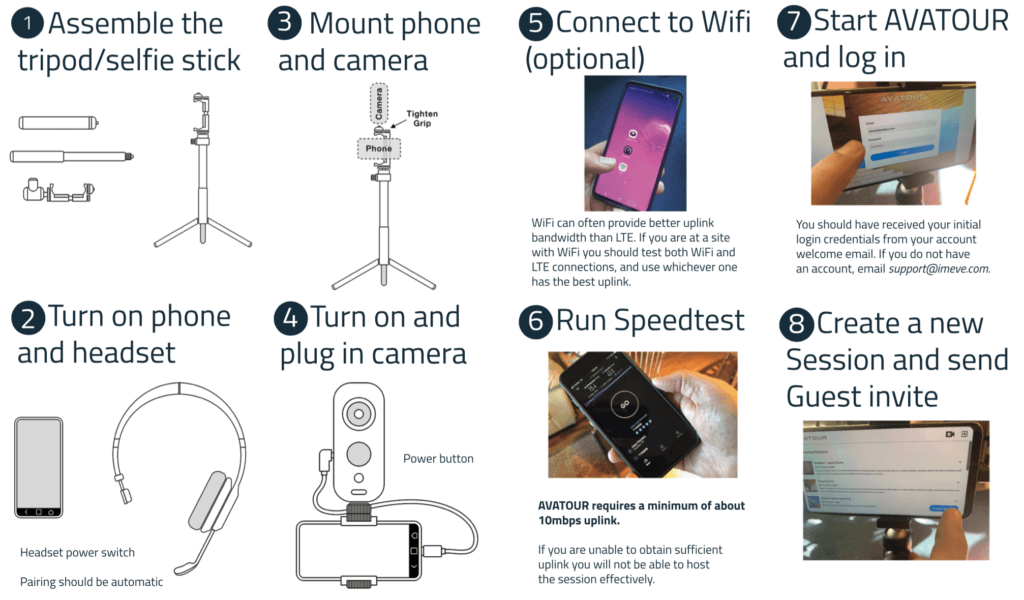

Provide Turnkey Trial Hardware

It’s that simple. If your product requires hardware, give it to your trial customers. Make a pretty box show up on their doorstep via FedEx, and make sure it has everything they need to get started right away.

In response to our flailing first Beta users, we created the “Orange Kit”:

This contains everything needed to run an Avatour session, including a tested and validated Android phone with working high-bandwidth LTE (or even 5G) cell service. Our second wave of Beta customers got this box.

The effect on our user feedback was immediate and obvious. Users who didn’t get the Orange Kit took typically about 10 days and repeated contact to get up and running; some users who got the Kit were literally operational within minutes.

If your product requires hardware, send it to your trial users as part of the trial.

Mistake #3: Your MVP isn’t minimal enough

Another startup shibboleth is the minimum viable product or MVP — the least amount of functionality that delivers actual business value. The final mistake we made during our Beta program was one that I know I’ve made before, which makes it all the more galling: our MVP was more complicated than it needed to be.

There’s a reason why this error is so common among startups. Especially in the early stages, startups tend to mostly be made up of engineers. Even the salespeople are tech early adopters. Everyone on the team thinks nothing of, for example, setting IP addresses. “Simple” has a very different definition for the dev team than it does for the customer.

In our case, that gap is particularly large. We intend for Avatour to be used by field personnel across a wide variety of industries — busy people who don’t typically configure software, don’t have time to read manuals and will give up on something before learning how to set an IP address on it.

While we were setting up our Orange Kits, we also made an effort to streamline and simplify our MVP’s user interface – removing some duplicated functionality, replacing some options with defaults, creating an automatic log in option. We were really proud that we were able to print up a “Quick Start Guide” to go with them – something that allowed users to get up and running in only ten steps!

To be fair, we had made a lot of progress. 10 steps is a lot simpler than our first prototype was. But it turns out it’s not minimal enough.

After having this new, simpler system in the field for a little while, we interviewed one of our Beta customers, a senior project manager at Gap. He made clear how far we have to go:

General contractors in the field will just give up on something if it’s too difficult. 10 steps is too many. It needs to be three – MAYbe four.

Ninad Athavale, Gap

He wasn’t the last customer we heard this from.

It turns out our minimum viable product wasn’t minimal enough. We built in functionality for session invites and management that just isn’t important right now, and gets in the way of usability. We find ourselves in the strange position of having to reduce the functionality in our next release.

The lesson here? When designing your MVP, be ruthless about what minimal means. Doing this right has a double benefit: it doesn’t just make your product easier to build, it also makes it easier to use!

Mistakes are part of the process

So, those are a few mistakes we made during our Beta program. I hope I might be able to help some folks skip these particular lessons. But mistakes like these are part of the very nature of running a startup during the product-market fit phase. When pioneering a new product category, there’s no roadmap to follow. Mistakes, to paraphrase presidents, will be made.

I’m sure we’ll make more mistakes as we continue the development of Avatour. In fact, we need to make mistakes. Mistakes are how we learn.

Running a startup is all about establishing and testing hypotheses, doing it quickly, and (crucially) not running out of money while you’re doing it. If you pay attention, you can learn as much when you’re wrong as you do when you’re right. Make mistakes, learn quickly, modify your hypotheses, and repeat. That’s the algorithm for getting to product market fit.